EMS Perspectives: An OpEd Page on the History and Future of EMS

By Clayton Kazan, MD, MS, FACEP, FAEMS

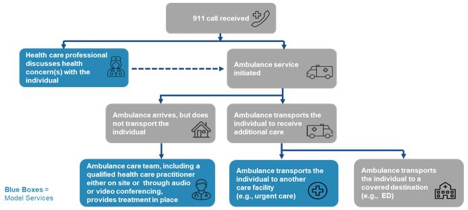

So we are about 54 years into the pilot project that is EMS and paramedicine. That we would even exist, much less thrive, years later, was viewed by many as highly improbable at the time. The EMS system, in its inception, was a complicated system with a lot of moving parts. It wasn’t simple, but it was fairly linear. Call was made to the Fire Department (or EMS, as 911 did not exist), a response was dispatched, units arrived on scene, they provided whatever assessment and treatment were appropriate (rudimentary by today’s standards), they notified the hospital, and they transported. The system of today has moved from complicated to extremely complex, affecting each of the steps above.

One of the notable exceptions, at least until recently, was the 911 system. We reduced the number of phone numbers down to a single, 3 digit number. This is a terrific example of system leadership advocating to reduce system complexity. 911 is in place throughout the US and enables you to access the appropriate local resources without knowing the local telephone numbers. From rotary phone to iPhone, the 911 system remained simple to the user. Now, with the advent of 988, we are reintroducing system complexity, and not just by giving the public a second number to dial. Bridges between the 911 and 988 system need to be developed to appropriately move traffic when the public dials the wrong number. But, I digress, because at every other step above, through system entropy and evolution, we have introduced complexity exponentially. From emergency medical dispatch to tiered dispatch to specialty response units to sophisticated assessment tools and new treatments, to new methods of hospital notification, and to the hyperspecialization of receiving hospitals, our system has become quite a wonderful beast. With every layer of complexity that is added, we create new ways for the systems to fail, but we have also created an infinite way for the EMS system to aid.

So, with all of that said, the question that I have been pondering and what drove me to my laptop on my day off was this…has the complexity of our operations failed to keep up with the growing complexity demanded of it by the communities we serve? We keep being asked to do more than EMS, to the point that EMS and prehospital care do not even seem to be the appropriate terms for what we do anymore because, so often, the E does not apply, and not all care that we provide should be prior to arriving at a hospital. Really, what we have become is mobile health, with traditional EMS existing as a service line under that umbrella. Nothing made this clearer than the pandemic response. EMS (or whatever we decide to call it) rose to the occasion and demonstrated amazing resilience and adaptability when so much of the healthcare system crumbled around it. We were the innovators. Why? Because we are still a pilot project. Traditional healthcare has been around for 2400 years, and it is more rigid, yet brittle. 54 years in, EMS is still trying to find and define its niche, which is why the adage, “if you’ve seen one EMS system, you’ve seen one EMS system” applies. You can’t say that for hospitals, Emergency Departments, clinics, etc. They’re more like Starbucks…pretty similar but not exactly identical and very expensive to visit.

So, what do I mean by this complexity gap? The cracks exposed in our healthcare system from the pandemic are far from repaired, and it remains to be seen how traditional healthcare will morph as it recovers. But, we have true crises of mental health, substance use, homelessness, aging population, and eroding access to all forms of scheduled medical care, and I do not use the word “crisis” haphazardly. We have more care facilities, of all kinds, calling us because they can’t get access to other forms of healthcare and are unwilling to shoulder the liability of watchful waiting when a free solution (at least to them) exists just three digits away. Our pace of innovation to meet these needs has been unable to keep up, and the end result has been more and more call volume driven, mostly, by low to medium acuity patients. As we seek new solutions, we run into perpetual problems with funding, reimbursement, and outright pushback other medicine stakeholders, who lack any granular solutions, seeking to contain any perceived expansion of the mobile health mission and scope.

Complexity can definitely be problematic, but it also generates a broader repertoire of solutions. We need to take advantage of our relative youth, amongst the rest of the house of medicine, with all of the optimism and adaptability, and keep advocating for innovative solutions, new connections to care, new treatment modalities, new delivery models, and new transport destinations. The going will be hard, but the alternative is the unfettered crumbling of our existing healthcare system and its growing inability to meet the needs of its constituency. We have come a long way in 54 years, but we have a long, hard road in front of us as well.

Website Layout and Graphic by EMS MEd Editor James Li, MD